While it might seem obvious, before New Zealand can start to sensibly plan how it can defend itself, it needs to ask and answer the question, “What country could be a military threat to New Zealand?” Many New Zealanders would respond by identifying China as a threat.

The author believes that China is the only suspect. There is no other plausible nation that is a near/medium-term risk. Some might hold back from labelling China a risk, , taking the view that it is impossible at this stage to foretell with any specificity what sort of action involving China New Zealand would need to be concerned about and be ready to respond against. Others may consider China a danger even if they cannot put their finger on exactly what form the risk might take.

Some individuals may recognise the existence of risk but feel powerless to address it; they might question New Zealand’s capacity for self-defence. This position is not without validity. Even those who see China as a risk encounter real difficulties in coming up with a feasible plan for New Zealand to defend itself against China. It raises a matter that deserves separate treatment and will be discussed later in the paper.

The following analysis does not make detailed predictions such as where and on what date hostilities might arise. But it is still possible to evaluate whether a particular scenario is one that actually could lead to hostilities or not. From that, we can see the range of possible flashpoints and extrapolate the nature of the conflict New Zealand could be pulled into and how it should prepare for it.

The possible risks

This part of the discussion is based on the following assumptions. First, China is on course to achieve its desired objective of establishing military hegemony in the South Pacific. Second, it will be ready to use force against New Zealand and other nations to achieve its goals. Third, China could pursue a specific course of action in the South Pacific that seriously prejudices New Zealand’s interests and fourthly, New Zealand believes the issue is so significant that it has to resist.

Why is China to be feared? In the first place, China’s profile in 2025 is not reassuring, as can be gathered from the following facts. First, China has shown its intent to resolve the Taiwanese dispute with its much less powerful neighbour by force.

Secondly, while some may consider that Taiwan is a case where China has an exceptional entitlement, there is no such excuse for the second key fact, which is that China is deploying thinly veiled military force in the South China Sea, particularly against the Philippines and Japan. In that contest, it has deployed its so-called “coast guard” vessels to force the Philippines out of disputed areas. The dispute with the Philippines is part of China’s larger ambition to establish exclusive control over the South China Sea, which would enable it to control navigation through these waters. China is unable to point to any pre-existing legal entitlement recognised by international law that could justify it displacing the Philippines in this way. To the contrary, in fact, in January 2013, the Philippines initiated arbitration against China under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), challenging the legal basis of China’s “nine-dash line” claim, which covered much of the South China Sea, and Chinese activities such as land reclamation and interference with Filipino fishing and oil exploration. China boycotted the proceeding, asserting its right to unilaterally determine its entitlements. The international arbitral tribunal that handled the claim ruled against China. China has continuously acted inconsistently with the arbitration findings.

Thirdly, a peace-loving nation would not, as China has recently done, without notice deploy naval units into the Tasman Sea, where they conducted rocket firing and other exercises. Most commentary would agree that the exercises were performative in nature and not justified by any military exigency. They were a show of force.

Fourthly, there is the treaty China recently concluded with the Cook Islands that explicitly mentions cooperation in building port infrastructure as part of a broader partnership. allow for the possibility of basing military ships, as has happened at the PRC military base in Djibouti, as well as in Sri Lanka and Cambodia.

Again, it is to be borne in mind that absolute proof that the Chinese intent is an aggressive one is not required. Instead, the enquiry is about whether these facts establish the existence of a risk. Many New Zealanders would, on these grounds, probably answer in the affirmative and say that New Zealand should be concerned about why China is militarily interested in this part of the world, which poses no threat to it. They would keep in mind that, based on its past conduct in the China Seas, China’s presence in the region justifies concerns about a future military risk to New Zealand.

Foreign policy experts disagree on whether modern China has hegemonistic ambitions. The first expert selected is Professor Yan Xuetong, a leading academic at Tsinghua University in China, who considers it an open question whether China will become a hegemon or may still evolve into the “humane authority” he hopes for. A “humane authority,” as opposed to a hegemon, is a powerful state whose material capabilities are unchallengeable but who embraces a completely defensive military strategy and takes care of the interests of other countries.

In contrast, an American academic, John Mearsheimer, is highly sceptical about the possibility of a peaceful rise for China. He asserts that, as China becomes more powerful, it will attempt to diminish the influence of the United States in Asia and dictate the boundaries of acceptable behaviour for its neighbours. While he does not predict that China will launch wars of conquest, Mearsheimer expects that it will try to push the U.S. out of the Asia-Pacific region and seek military superiority over its neighbours.

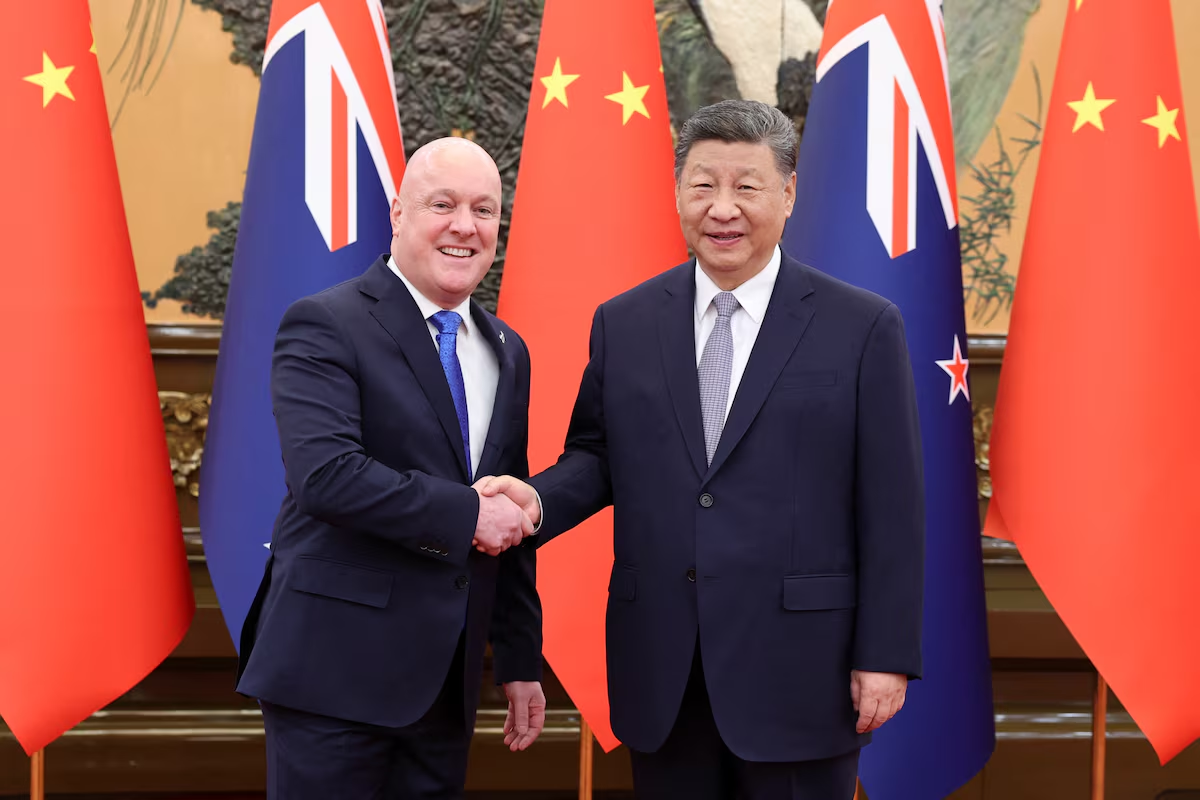

In New Zealand, Associate Professor Brian S. Roper, in his writing on the subject of New Zealand’s position between the great powers of the US and China, considers that the current conservative government’s strategic direction is based upon pro-American narratives, which are inevitably anti-Chinese. He acknowledges that the rise of China has important implications for New Zealand as governments walk a tightrope between increasing economic dependence on China and traditional security, military, and diplomatic relationships with Australia, the UK, and the US. He considers that New Zealand’s current foreign policy post is anti-China and unjustifiably advocates closer ties to the US. He argues for a shift towards non-alignment and neutrality in future conflicts.

On one live issue, Associate Professor Roper says, accurately it is thought, that the consensus in the literature is that ‘New Zealand has adopted an asymmetric hedging strategy to manage the fact its key security and economic needs have diverged, requiring positive relations with two competing sets of actors—traditional partners for security and China for trade’[1].

This writer considers that on the balance and based on what we know about contemporary China, it should be viewed as a military risk and that New Zealand could in the future be exposed to military pressure from it if it failed to fall into line with what China wants. That is, now that China has arrived in New Zealand’s neighbourhood, it can be expected that this very powerful state which has a track record of using military power—or the threat of it—to get its own way, will replicate that conduct here. There is no reason to suppose that New Zealand is an exceptional case that would attract less confrontational treatment than Taiwan, Japan, or the Philippines. It should therefore plan on the basis that China poses a threat.

The fact that China has proved itself capable of behaving in such a way does not, however, establish to a level of certainty that it will actually do so. Whether New Zealand will prove to be at risk of future hegemonic action can only be analysed by looking at some of the circumstances that might provoke such conduct on the part of China in the South Pacific, and it is to that that attention will be given next.

Taiwan

There is a risk that hostilities could break out between the two prime protagonists who are concerned with Taiwan, namely China and the United States.

Rather than launching an outright invasion, many experts believe that a more likely outcome is for China to impose a blockade on Taiwan, effectively cutting it off from the outside world. A blockade would prolong the Taiwan conflict more than a Chinese invasion would. The outcome would be largely similar, as a blockade would rapidly result in US involvement and an escalating military conflict. The difference between the two outcomes does not need to be further commented on

New Zealand is not a major trading partner of Taiwan. Protecting its trade with Taiwan as a trading partner would not be sufficiently serious on its own to justify New Zealand taking up arms over Taiwan.

Either way, if there is a blockade or invasion, it would result in a closure of the South China Sea in the vicinity of Taiwan with a resulting constriction of trade routes to China, South Korea/the Republic of Korea (RoK), and Japan, which could affect New Zealand. It would plainly be in New Zealand’s interests if China could be deterred from taking the first step, which could lead to such a state of affairs. But whether or not China would be deterred would not be affected by New Zealand’s added presence in a coalition of Western forces ranged against China; it would not add significantly to the deterrent effect already available. New Zealand would benefit from normalcy in the South China Sea, but joining a coalition would not help, even if invited and able to join, which it isn’t.

A further factor to consider is that a major factor shaping America’s explicit justification of US support for Taiwan is that such a step is required to uphold the international rules-based order, including the proscription of states invading other countries as they choose[2]. That is not to say that the US position is entirely principle-based: a further, non-articulated, driver of America’s involvement is that other regional nations which are hedging their position will be looking with interest to see whether America prevails over Taiwan.

But New Zealand has itself repeatedly referred to the rules-based order when articulating what it stands for. Without expressly stating support for Taiwan, New Zealand has in recent times, including in conjunction with Australia, made statements recording its opposition to unilateral action over Taiwan and to the need for peaceful resolution of cross-strait issues without the threat or use of force or coercion[3]. A need for consistency between such stated principles and New Zealand’s actions would suggest New Zealand should support the US in Taiwan on this ground.

Additionally, should New Zealand wish to align itself defensively with the United States as an ally (an issue discussed elsewhere in these articles), it would be tactically unwise for it to do nothing to support the US until its defence interests were directly affected. The current US administration would likely detect any perceived failure on New Zealand’s part. However, this does not imply that the US would anticipate New Zealand’s direct military involvement in the Taiwan conflict. It is unlikely that it even expects Australia to be so involved. Its role would be in areas such as basing US forces if necessary and supporting the US with intelligence via its Pine Gap and North-west Cape intelligence sites.

In the end, though, the question of whether New Zealand should take up arms in solidarity with the United States and other Western countries is academic for many practical reasons. First, New Zealand is not bound to participate in those hostilities and probably shouldn’t because its immediate strategic interests are not involved. Second, there are practical reasons against it: New Zealand will not, in the near or medium term, be in a position to fight in what would be a primarily maritime-centred conflict because it does not have any suitable ships that would foot it in a contemporary sea battle. Even if it did, it could not deploy them to the scene of a battle some 7000 km from New Zealand shores.

Summary to this point

The discussion will continue in the next article, where the focal point will move to looking at other specific situations in which a risk in which hostilities with China may arise at some point in the future.

[1] Cting another New Zealand academic who works in this area, Associate Professor Steff.

[2] Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter

[3] Such a statement was made in August 2024